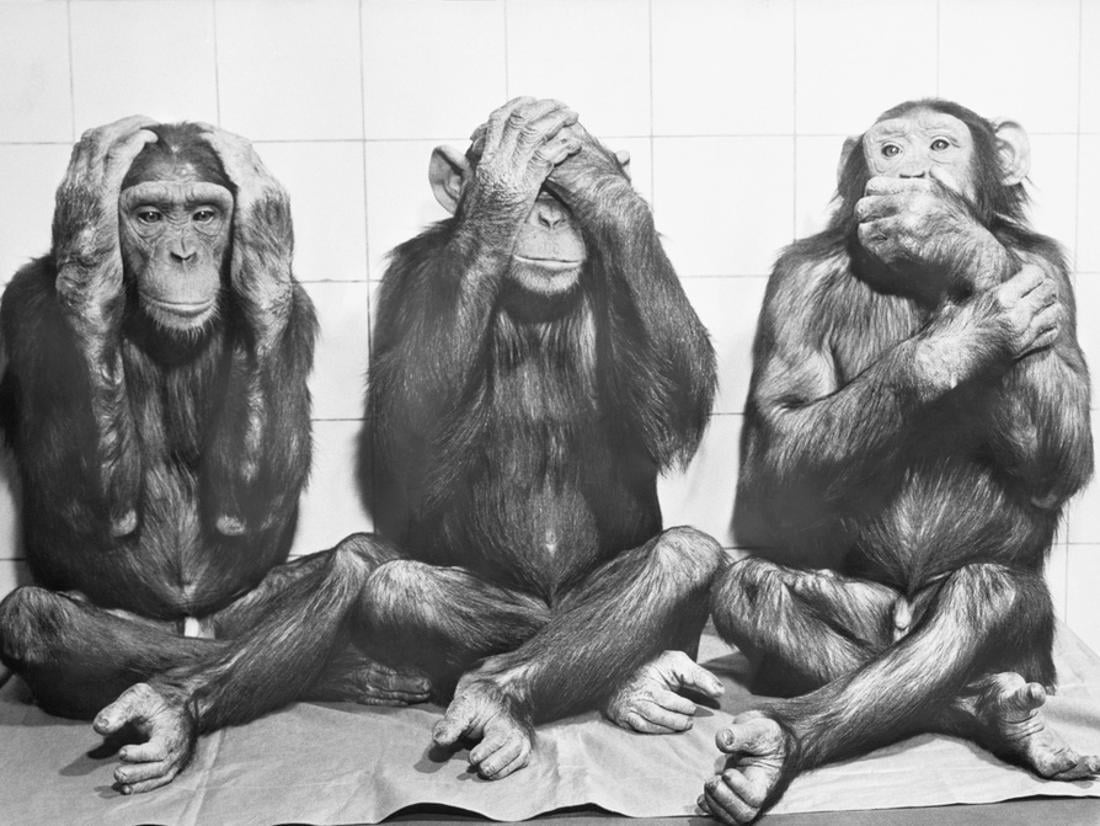

A Buddhist monk from China introduced the "see no evil' concept into Japan. Horse caretakers were expected to be loyal to the samurai, like a squire to a knight. Caring for a samurai's horse was a sacred duty. They embody the old saying “See No Evil, Hear No Evil, Speak No Evil.” Samurai were ferocious warriors when mounted on horseback and, in feudal Japan, horses were rare. It held the painted panel carvings of the Three Wise Monkeys over the stable doors. The horse stable at Tokugawa Ieyeyasu’s masoleum was also a national treasure. Bolstered by a can of piping-hot buncha tea from a Pocari Sweat soft-drink vending machine labeled "attakaii" for hot drinks, we strode to the nearby stable. One reason you would look all day was that many of the Yomeimon Gate's figures were parts of plays and story-telling theatrical scenes. Lucas heard the Japanese word “jidai,” meaning “age” or “time period,” and he came up with “Jedi” for his Star Wars knights. Does this sound familiar? Talking to park attendants, we learned that George Lucas based his Star Wars themes on the samurai culture in Japan. While there was harmony in life, it was always threatened by evil spirits, who must be kept at bay.

To Shinto believers, the world was good and people were good. The second part, “tō,” means “way” or “art.” Think of Shinto as “way of life,” or “way of the Gods.” Shinto embodied a Japanese native belief system that cherished one’s ancestors and the spirits of nature called “kami.” Kami existed in both divine and earthly forces, including plants, animals, mountains, and stones. Shinto shrines, like Toshogu, were built throughout this UNESCO World Heritage Center, and art culture is central to the Shinto faith. There were many works of reverent art at Nikko. A warrior and king, Iyeyasu Tokugawa's presence remains vibrant and his image is deified in many of the temples and shrines. This most famous Samurai (soon to be featured in an FX film based on James Clavell's novel and shot in Japan) this Shogun gathered builders and craftsmen from all over Japan to construct his mausoleum at Toshogu Shrine. Some objects were marked with the Japanese katakana character for samurai and with Ieyasu's logo. W e marveled at Ieyasu’s armor, swords and household objects in the temple collections. I was shaking as I photographed the open-mouthed guardian on the right side of the gate, the Misshaku Kongō, but my tremors came more from the freezing January chill than from statue-induced terrors. These gate guardians were carved with fierce expressions that were meant to terrify evil doers. At the temple entrance, the ornate gate has two Niō, wrathful and muscular guardians of the Buddha. The Nikko Toshogu temple was built to immortalize Ieyasu Tokugawa (1543-1616) one of three "Great Unifiers" of Japan.

Shivering, we kept the cameras turned off and just stared at the gold-leafed Buddhas. Worshiped for over two thousand years, the Buddha figures are sacred representations of three local mountain peaks. These Buddhas were off-limits because their temple housed a hallowed mausoleum. W e walked under the three 16-foot high wooden Buddhas. “Doh” meant hall and “Sanbutsu” meant three Buddhas. Inside, we inhaled an ancient aromatic combination of incense, mildew and lacquer.Ī priest named Jikaku built this temple, known as Sanbutsu-doh. After leaving our hiking shoes by the doorway near snow-and-moss-covered rocks, our sock-clad feet slid easily across the polished wood floor of the outer hall. Ī sign outside the sunlit temple read “No pictures of the Buddha, please.” "Okay," I thought, at least it will be warm inside and my hands will stop shaking. We arrived in the winter when the mists settle around sacred temples and shrines around Mount Nikko. With some exceptions, our cameras were welcome in most shrines and temples. Since Nikko’s humidity was hard on electronics, all gear traveled in Ziploc bags with moisture absorbing pads. For the whole trip, I'd packed only a couple lenses, with wide and medium focal lengths, and left the tripod behind. From Tokyo, we traveled about 120 kilometers to Nikko on the efficient Tobu-Nikko Line train. We stayed at the Nikko Kanaya Hotel and we left all our optical gear there but one camera and one lens we packed for a day's photographing. We'd come to Nikko (NĒ -KŌ) to photograph its sites, to walk along the racing Daiya River, and explore old Japan. The name of this building translated as “light from the East” and it symbolized the dawn of a new born nation: Japan, land of the rising sun. Basho's eternal sun light glowed along on the stairway handrail as we walked up the steps of Toshogu temple. In his notes, Basho recorded that the word "Nikkoo" meant the bright beams of the sun. On his travels through northern Japan, the poet Matsuo Basho made Nikko his 5th station stop.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)